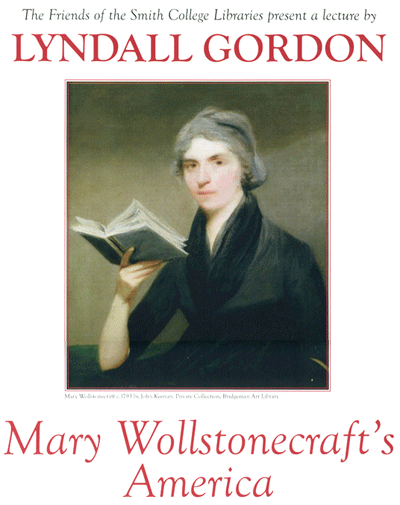

Mary Wollstonecraft’s America

Summary of a talk (derived from Vindication: A Life of Mary Wollstonecraft) at Smith College, Northampton, MA and at Notre Dame University, Indiana (October 2005)

John Adams said of Mary Wollstonecraft: "She seems to have half a mind to be an Englishwoman, yet more inclined to be an American."

Mary Wollstonecraft never came to America, but she did imagine it in the 1780s and 1790s, and did plan to emigrate with her American partner, Gilbert Imlay. They intended to farm on the frontier, and she would have done so had not Imlay withdrawn. Her youngest brother, Charles Wollstonecraft, had already settled in the territory of Ohio, and Mary had sold family property to buy land there. She wished to join him, and to bring along her two sisters, Eliza and Everina.

The first part of the lecture opened up this possibility on the basis of Mary’s tie to Imlay. He appeared as a frontiersman, a new breed of man to match her sense of herself as "the first of a new genus" of womanhood, which she spelt out in a letter to Everina in 1787, a novel Mary in 1788, and most fully in her famous Vindication of the Rights of Woman in 1792. The lecture countered the reductive image of Imlay as scoundrel with a more complex portrait of Imlay as the writer of a respected book on the frontier and as an upholder of values Wollstonecraft shared: an abhorrence of slavery and militarism; a regard for native Americans; and sympathy for women trapped in a marriage contract that denied them basic human rights.

Imlay and Wollstonecraft met in Paris in 1793 as the Terror took hold in the wake of the French Revolution. He declared her his wife at the American Embassy – by conferring his nationality on her, she was saved from the fate of her fellow-countrymen who, as "enemy aliens", were thrown into the Luxembourg prison. From this time she began to live with Imlay, regarding their tie as "sacred."

She had met Imlay with a prepared mind, a pro-American ideology. The lecture moved on to propose that the prime importance of America for Wollstonecraft was not personal but political, and preceded her attachment to Imlay by nearly ten years. There followed a backflash to her years as a schoolteacher in Newington Green, two miles north of London, in the mid-1780s. Newington Green had been sympathetic to America throughout the War of Independence. I suggested that Mary Wollstonecraft had been policiticized by a Unitarian minister the Revd Dr Price. He looked on the American Revolution as "the fairest experiment ever tried in human affairs."

In 1785, when John Adams arrived in London as the first American minister to the court of St James, he and Abigail joined Dr Price’s congregation. Mary Wollstonecraft was there at the same period, listening to a gentle voice that urged reform on the model of the Americans who had "established forms of government favourable in the highest degree to the rights of mankind." The rights of womankind were no more than a logical step from what Dr Price preached.

The lecture then went on to explore the larger question of transmission across the Atlantic: ideas transmitted from America to Europe where they took on a life of their own. How did Wollstonecraft translate what she understood about the American Revolution into a politics of her own, not only the rights of women, but also the "new genus" of womanhood that she was trying out in each phase of her experimental life? This question leads to the further question: how those politics of gender are transmitted back to America. The final part of the lecture explored the different responses of John and Abigail Adams to Wollstonecraft’s books, with John teasing Abigail as a "disciple of Woolstoncraft" [sic] , and Abigail’s spirited retorts: Adams "prudence", she argues, might benefit from Wollstonecraft’s idea of an alternative civilization based on "domestic affections" rather than governance based in contests of power.